2D or bitemporal Historization: A primer

In this series

- 2D or bitemporal Historization: A primer

- 2D-Historization in a graph database

- Simplify the bitemporal Neo4J query with a user-defined function

When it comes to time & software systems, there are three major categories:

A system that needs no notion of time

A primitive filesystem manages what is contained right now. It does not care about what files you had one month ago, and it certainly wouldn’t know what files you’ll have in a month.

A system that contains historical data

More & more systems fall into that category. Whenever we interact with software that is interested in us as a customer or as a product, it will like to keep past information about us, not only to provide us with e.g. our order history, but to identify patterns within our interaction with software.

A system that allows past and future alterations

In a number of systems we need to define changes that will be happening in the future, as well as changes that are retrofitted to have happened in the past. Your boss may have decided three weeks ago that you will get more stash starting 2017. This may have already been recorded in the book-keeping software system of your choice.

Sometimes you may be presented with new information about past events and you want to enter it into the system at the specified date. Martin Fowler has written about this already. The take away of such systems is that we need to record two times for those system changes that we are interested in. Martin calls this the recorded and actual time. The recorded time is the time at which the new information enters the system. The actual time is the one that is relevant to the business modeled by the software.

Such a system now allows us to record changes that occur in the future or in the past. The 2-dimensional nature of such a time point also allows us to ask questions like “How did the state look like one month ago?”

Let us reason about such 2D-time-modeling or bitemporal history of our domain with code:

type TimePoint<'S> = { recorded : int; actual : int; state : 'S;}Any state shall be contained with information when this state was recorded as well as when its validity starts. Often the actual state changes will have a granularity of days, while changes may occur multiple times in a day, forcing a higher granularity on the recorded field. We’ll just use ints for now (think Epoch).

When we make a query as to the state of the system we will need to specify for which point in time we want the answer. Hence, our historical data will only show states alongside their actual dates:

type HistoryEntry<'S> = { time : int; state : 'S;}

type History<'S> = HistoryEntry<'S> listA situation where we successively store changes may look like that:

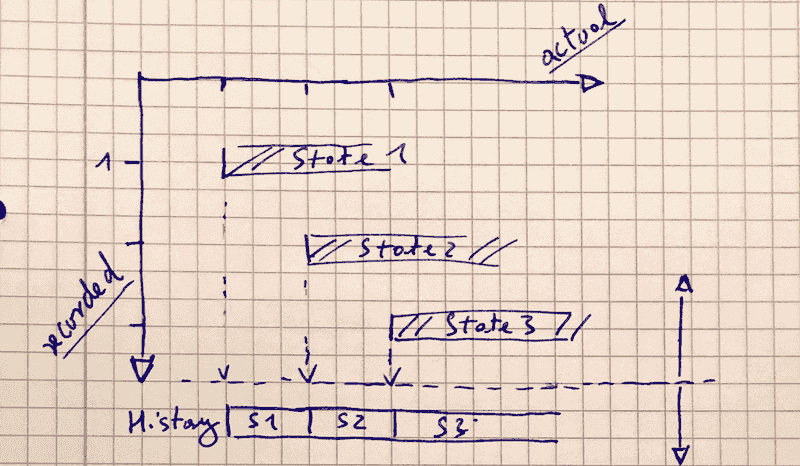

let chain1 = [ { recorded = 1; actual = 1; state = "First" }; { recorded = 2; actual = 5; state = "Second" }; { recorded = 3; actual = 7; state = "Third" };]Illustrating such data is typically done with 2 axes:

The dashed line shows our “projection” of the history, which is drawn below. Also noteworthy is the fact that we define states open-ended. This is because the end of some state may be different depending on the time at which you project your history. If you look at the above example with date = 2, State “Second” will have indefinite validity, while the shown projections ends it when “Third” is introduced. Indeed, the “end” of some state may typically be a business concern rather than something that needs to be forced upon the modeling of bitemporal history

Let’s solidify the way we can project History from our states with code.

- Given a point in time

- Go backwards from that point along the recorded axis

- Collect all relevant states.

let recorded = 2 // the time at which we look at the statelet history = chain1 |> List.sortByDescending (fun tp -> tp.recorded) |> List.skipWhile (fun tp -> tp.recorded > recorded) |> List.fold foldHistory []foldHistory collects all those states that need to be considered.

let foldHistory<'S> history timePoint = let newPoint = fun () -> { time = timePoint.actual; state = timePoint.state } match history with | [] -> newPoint() :: history | historyEntry::rest -> match (historyEntry, timePoint) with | MustBeConsidered -> newPoint() :: history | CanBeIgnored -> historyGiven a certain condition, a new HistoryEntry must be considered and will be prepended to the list of already collected history entries. What is that condition? Consider the following state changes:

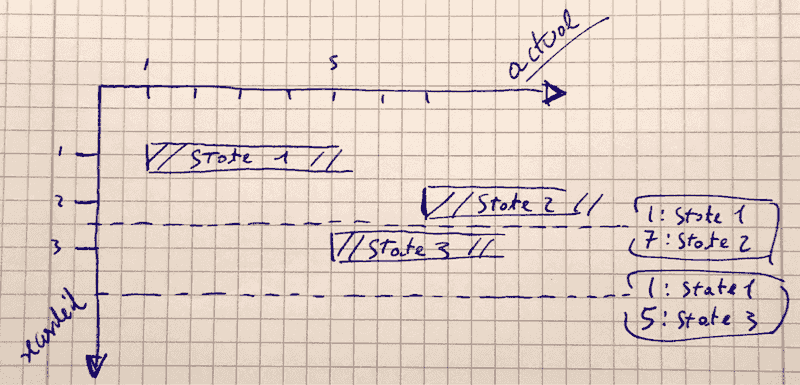

let chain2 = [ { recorded = 1; actual = 1; state = "First" }; { recorded = 2; actual = 7; state = "Second" }; { recorded = 3; actual = 5; state = "Third" };]

State “Second” is being superseded by a new state. In other words, depending at which point in time you look at the state of the system, State “First” is either followed by “Second” or “Third”.

Hence “Collecting the relevant states” means that while we move backwards along the recorded axis, only those states whose actual value is smaller than the one of the previously collected state will be considered.

let (|MustBeConsidered|CanBeIgnored|) (reference, newTime) = if (newTime.actual <= reference.time) then MustBeConsidered else CanBeIgnoredPerforming such logic in code, in-memory may prohibit itself when some object undergoes hundreds or thousands of changes throughout its lifetime. Having to keep time as a 2-Dimensional record complicates matters a lot in terms of e.g. persistence.

However, the logic behind it is fairly straightforward.