Porting a react application to typescript

I am not a great friend of javascript, to put it diplomatically. However, if you want to write a web application, most people will use javascript, because it is readily available across billions of devices.

There are many efforts to bring back sanity to application development. These are usually languages with a type system that get compiled down to javascript (purescript, elm, websharper, etc.).

One interesting middle ground is typescript, which gives you a nice path to perform a soft migration (an option I didn’t use), since javascript is also typescript. The value proposition for me is using a compiler that performs checks over a type system, sees whether I didn’t make anything up on the fly and whether I am using external APIs correctly.

Since I started work on a private project of mine using the react-framework on the UI-side of things, I was longing for at least being able to use typescript to bring a little bit of that safety net back which languages with a types-enforcing compiler give to you. The major showstopper was that I like to use jsx to represent a hierarchy of UI components but for quite some time there were only hacks around to reconcile jsx and typescript.

But apparently, the typescript gods saw utility in supporting jsx and now, if you grab yourself the nightly build of typescript, you will get the option to write .tsx files in which you can combine jsx and typescript!

It was time to port my stuff to typescript

git checkout -b tsnpm install typescript@next --save-devnpm install tsd --save-devnode_modules/.bin/tscnode_modules/.bin/tsdtsd is a nice additional utility to manage the download of d.ts files, those files that provide typescript definitions over popular javascript libraries.

A good way to use the typescript compiler is to provide it with a tsconfig.json file, in which all options and arguments to tsc can be placed. The following gist shows mine.

jsx: reactmeans that the jsx is converted to javascript in the compilation process. There is also the option to leave the jsx intact and just convert the typescript around and in it to javascript. Chosing this option means that there is no additional compile-step necessary.target: es5is the target version to which typescript will compile, in this case Ecmascript version 5. This is because you usually work with es6 idioms, to which typescript attempts to maintain high fidelity.

At first I was concerned that all files that you want to compile need to be explicitly stated. It turns out that once you use a module system, you pretty much just need to provide the entry points to the application and all dependencies are followed and also compiled. The other files are

tsd.d.tsis an aggregation that is created automatically bytsdwhen you install.d.tsfiles.Externals_shallow.d.tsa couple of extensions that I made myself on types provided by the.d.tsimports in order to support my use cases. As an example, I removed the descriptions for jquery-ui as it did not provide the API that I was talking to for those components in use. Here I chose a very shallow type definition.

Also noteworthy is the fact that if you choose a module system, typescript will refuse to create a single output file. In that case you will need to bundle it yourself (to which we come later).

Changing the code

As far as I can tell, importing and exporting follows the es6 nomenclature. Prefixing classes, interfaces and functions with export will make them available for consumption from the outside.

While I was at it, I changed the way I define my react components as seen in this gist:

I have heard of a few feeling molested by the introduction of a class concept in javascript. Having programmed many years in C# so far, with a good part of it in UIs, the abstractions as well as problems that this brings along are well known to me. If there is any place to package code into snippets of behaviour and data, then it is the UI. Hence, using the class construct here feels fairly natural.

Packaging and wiring it up.

I am not developing a single page application, hence previously I would create with browserify a common bundle and multiple bundles to represent the different areas.

I still use browserify for bundling but create a single common bundle (containing all the external dependencies) and a single app bundle, even though I have several entry points.

The entry points are the only thing that I register globally:

And that is the code in the gulp file that creates the app bundle:

Gotchas

I lost my state!

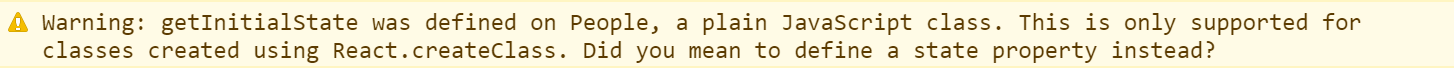

In a select few places in the code I was using the react lifecycle hook getInitialState() : Object - If I had studied the `.d.ts file for react a bit better, I’d have seen that this hook is not supported for components written as a class. I only noticed through broken behaviour and a very helpful warning of the dev-build of react…

It turns out that the right way is to initialize the state variable. Since you often derive your state from those properties that you get passed in during initialization, a good place to do that is in the constructor:

Once more: the return of the dislocated “this”

It seems that when you are writing something like <input type="button" value="hi" onClick={this.handleClick} /> in jsx, the react tooling would automatically add .bind(this)to the referenced function. A number of issues with the port to typescript had to with the fact that the typescript compiling wouldn’t do this for me, effectively letting my functions end up on the wrong this. To mitigate this I need to add the call myself - another source of error which cannot be statically checked.

However, I consider react-tools’ correction of this to be superior in this situation, such that I have asked the typescript team if this could be introduced in the parsing of the jsx.

Where is my router?

I am using react-router for those few routing needs I have. While it somewhat feels like using a railgun to kill a wasp, it does what I need.

One thing you need to do to have access to the router in rendered components is to state what you want in the component’s context.

var C = React.createClass({ contextTypes: { router: React.PropTypes.func.isRequired } ...});During the port this information didn’t seem to be evaluated anymore. Thanks to Marius Rumpf I found out that the contextTypes need to be defined as a static when using the class syntax:

export class AppFrame extends React.Component<FrameProps,any> {

static contextTypes: React.ValidationMap<any> = { router: React.PropTypes.func.isRequired }; ...}And presto, router was back on the context.

Why didn’t you warn me that there is stuff that isn’t there?

With great sadness in my heart I learned that .d.ts files can define static variables which are then assumed to exist in the context of compilation, the main culprits in my tech mix being jQuery and lodash. Since everything I am programming is a module that gets compiled and bundled up, I have nothing defined globally. While jquery is incidentally available globally (thanks bootstrap, thanks syncfusion), lodash’s _ is not. What happens then is that in a component I can accidentally start using _ and typescript will not warn me about it, since it sees the definition in lodash’s .d.ts file.

The resulting runtime error is pretty straightforward, but something in me dies a little for every runtime error I witness.

My opinion is that .d.ts should eschew any kind of global definitions, which would make the whole process much more module friendly. If a developer has an application where certain globals are defined, it is very easy to define jQuery’s and lodash’s globals yourself.

Why do we always want to be so clever?

The remaining errors are simple dev stupidity where in every refactoring you can run into the danger of trying to be clever and replacing code you deem ugly with an alternative that actually does not do the same thing. Not typescript’s fault

In conclusion

As I’ve stated earlier, for me typescript makes javascript tolerable. The fact that typescript now supports jsx has been the major enabler to make this port, I am definitely happy to have done it. Already I’ve found a few inconsistencies and superflous properties that TS was happy to point out to me, and while the code is obviously more verbose (as it has type annotations), it is much easier to understand and reason about.

There are still a number of errors that TS cannot currently catch but which a statically verified type system could catch, but I feel a definite improvement to my workflow when compared to using javascript directly.