Migrating data while being 'always on'

TL; DR; - Software systems evolve. Some software system should be ‘always-on’. These two constraints sometimes clash considerably. The following are some musings on that matter.

Software systems evolve for various reasons. The requirements change, used platforms, libraries and frameworks change. The team creating the software can change in size, or abilities. The sum of all this can be considered as the software’s environment. The rules by which evolution in software systems play out are different to the ones we see enacted in nature. In nature, systems that are fairly rigid in their interactions with the environment will produce large quantities of replicas with small variations, to have those survive that are most fit in their ability to interact with the environment. Also, nature has a (albeit huge, but) finite set of mechanisms to vary, store, retrieve and put information into practice. It can’t come up with a completely novel way to express certain mechanisms within the living creatures.

With software systems we often have one working system which needs to evolve. We can consider a new deployment to be the next replica which ideally is better adapted to the changed environment. It is in the interest of those growing the software that deployments are kept small, much like in nature - The environment usually changes continuously and hence our deployments should follow suit. In this situation it is relatively easy to be ‘always-on’.

Always-On: a software system that stays available to its users even during those moments were the software is being adapted to the environment.

Sometimes a change in the environment can be so severe that it breaks the assumption of being a continuous landscape. If the new environment ideally necessitates a change in the storage structure of the system alongside a data migration (something that doesn’t really happen in nature, imagine introducing a fith base to the DNA and rewriting the information with the new capability), ‘always-on’ can be a difficult attribute to attain. How do we deal with such a situation?

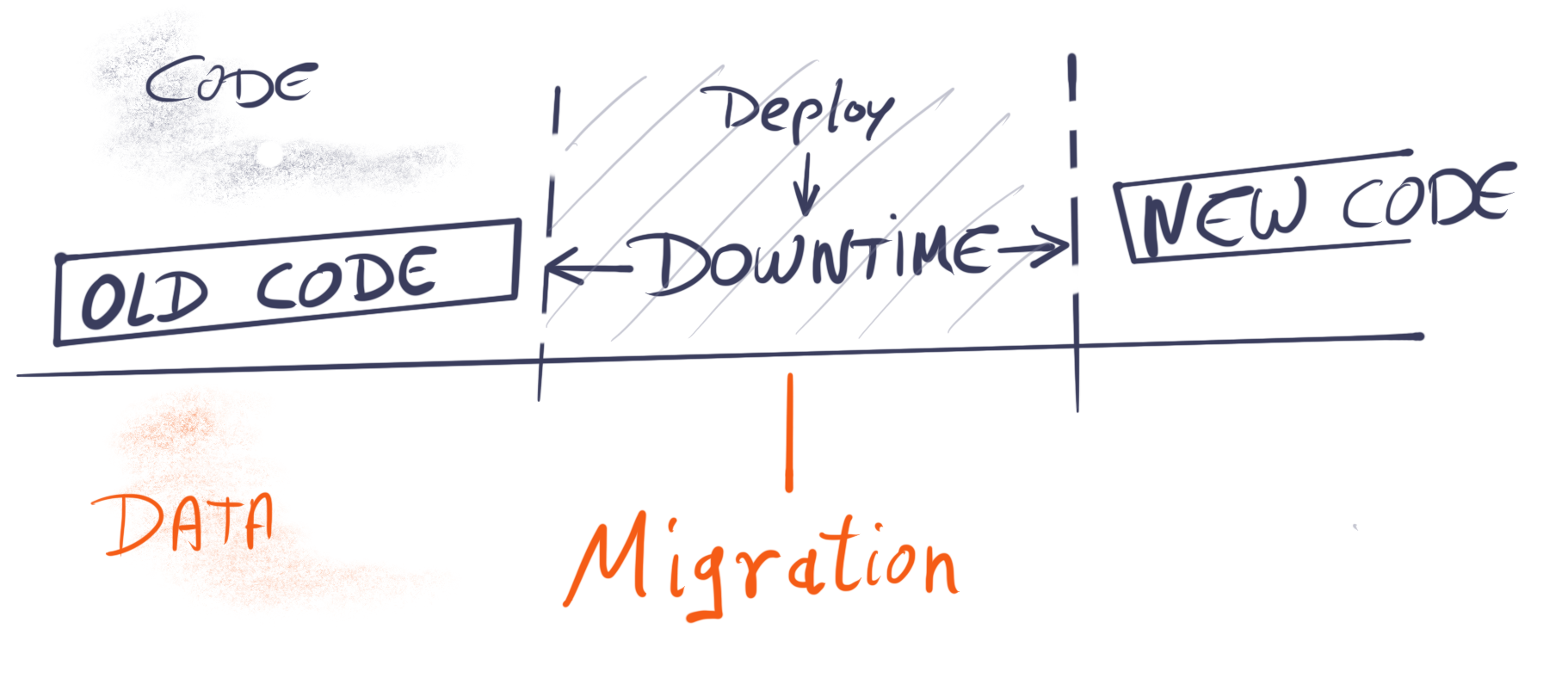

We suspend the ‘always-on’ capability, change the data, deploy the next iteration of the software and start it again. Because the software assumes the data to be in a certain way.

As users we’ve grown used to ‘always-on’-software systems. We scoff at web applications that tell us that during the next 2 hours the system will be unavailable, myself included. But, having been in the middle of such a discontinuous change in the environment during the past week, I can testify that being ‘always-on’ complicates matters quite a bit. How can we make sure that the system remains usable even though we change the underlying data structures? Our strategy in this case was the following:

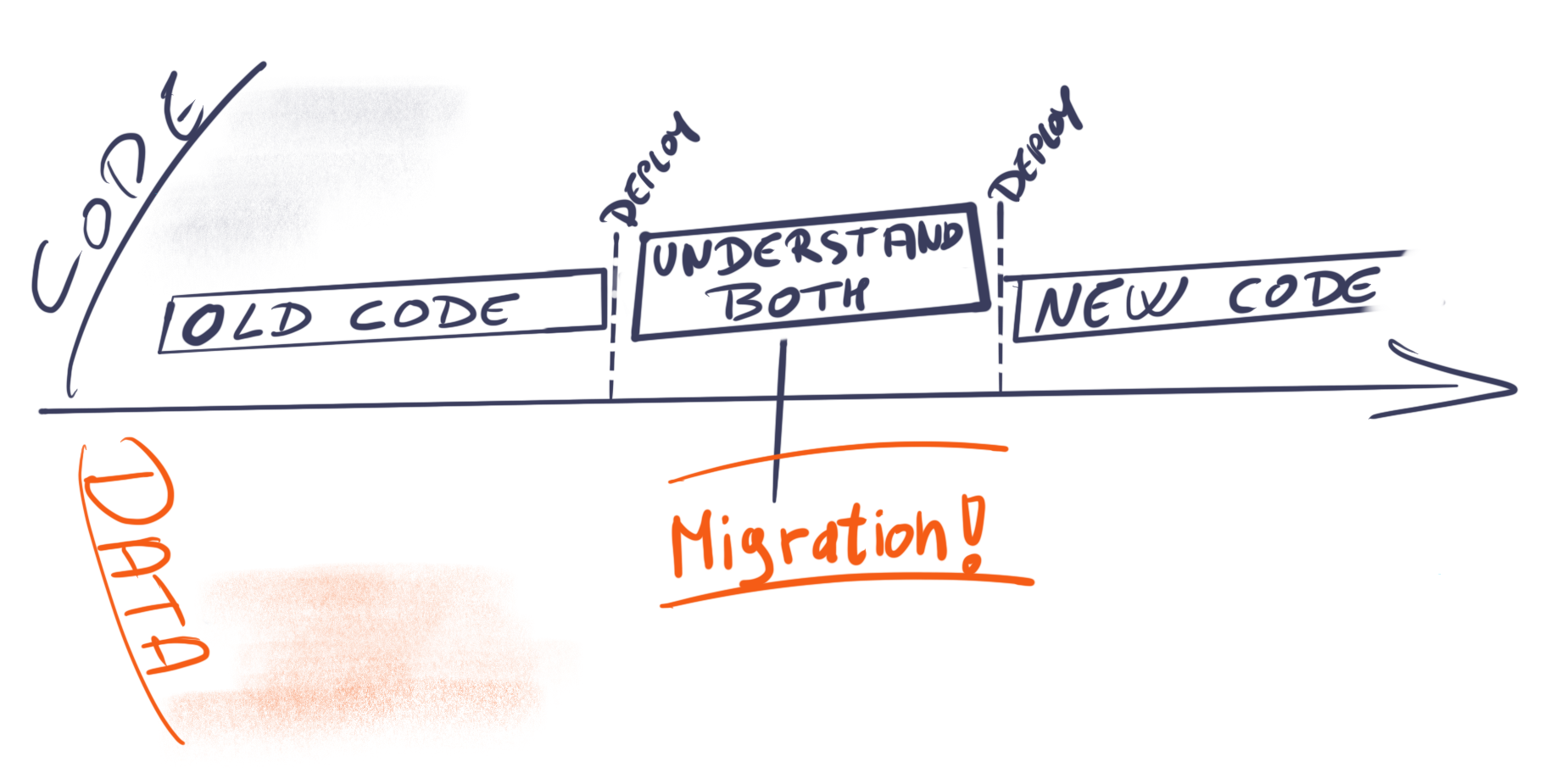

We deploy a version of the software that understands both old and new structure, then perform the migration to the new structures and then, at some later stage, deploy the software version that only understands the new way of doing things.

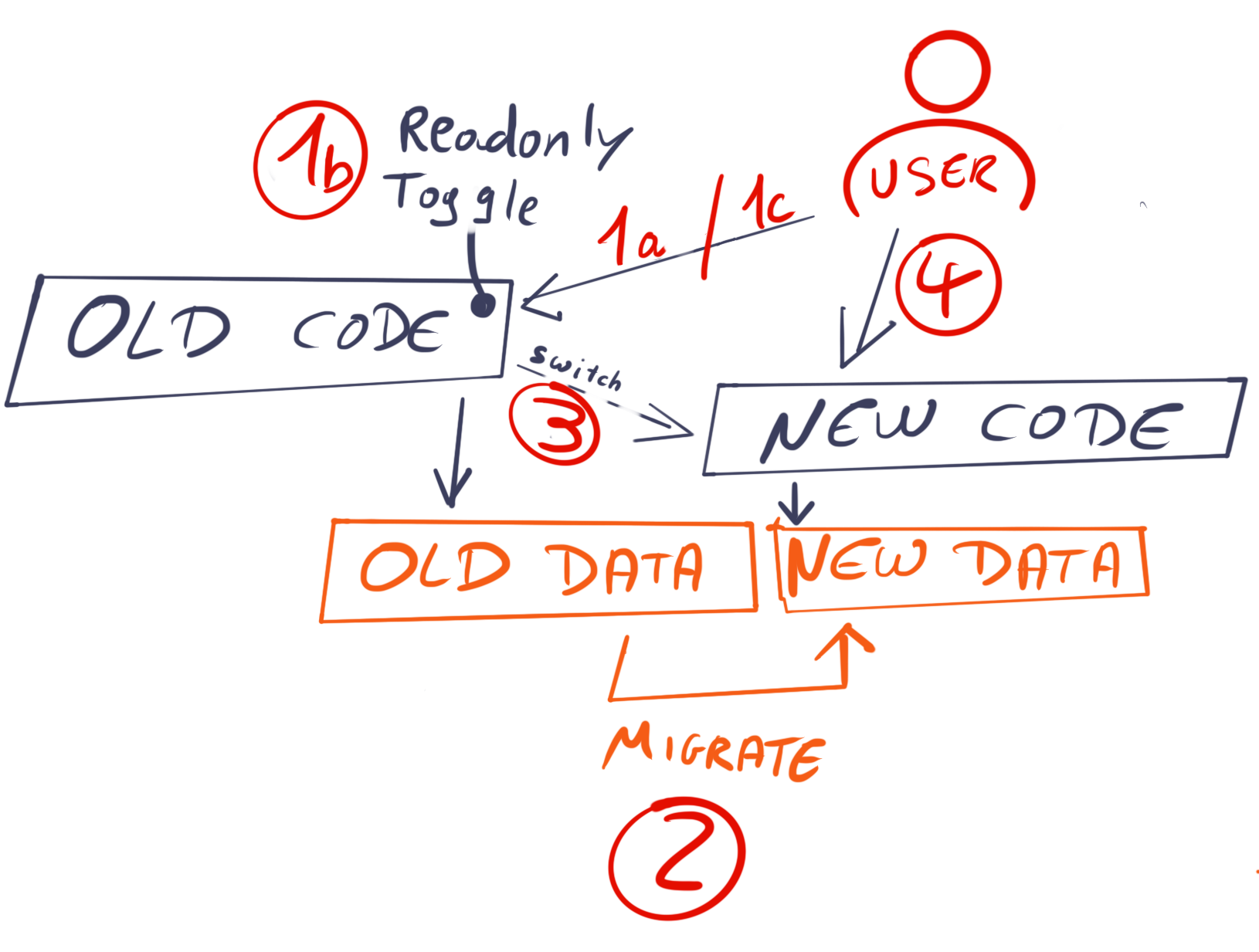

Depending on the particular change, some teams may provide a read-only copy of the old system, prepare the new one, and then switch over.

Giving a readonly version of the system can be a good choice if the usage of the software is asymetric anyway (far more reads than writes) and if it is relatively easy to duplicate tha data store, or if your read-model is expendable:

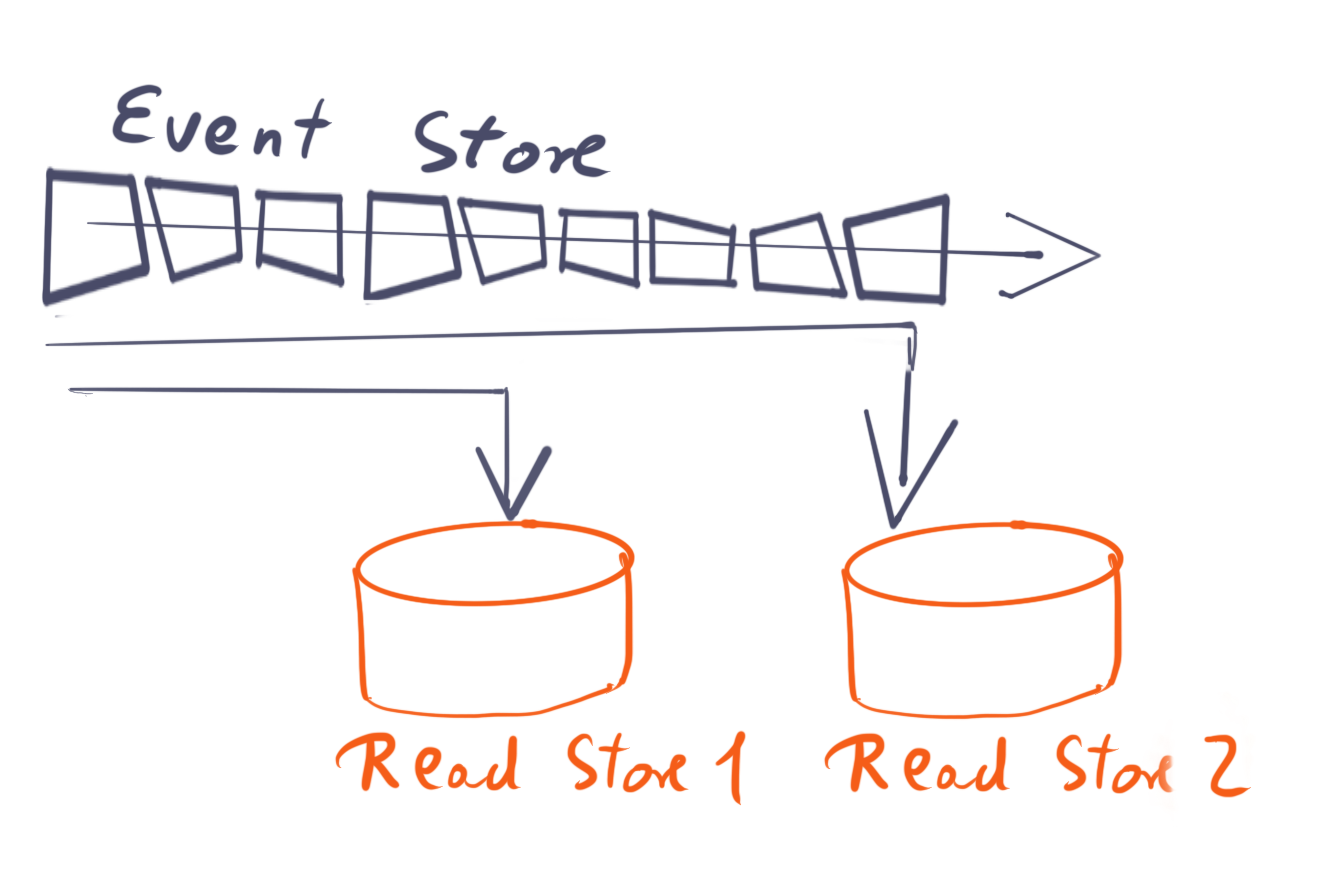

While I’ve never had the honour of working on an event store-based system, it seems that a different data structure of the read-model is easily attainable by creating a new projection from the relevant data and then switch to the new software. But what if you need to do changes to the write model? Changing something in retrospect seems to be quite the pain in this scenario.

The process of staying ‘always-on’ isn’t easy. In the past week it required numerous reviews, code tweaks and temporary solutions that can hit your ability to produce value to the software users. Stopping the time (i.e. downtime) and doing the necessary changes is certainly easier (provided you limit the deployment and changes to that which necessitates the downtime). However, many production systems don’t have the luxury to stop time.

- Users depend on the system 24 hours a day

- A readonly-mode means losing money because earning money usually requires a write :)

Hence the decision to be ‘always-on’ should be taken seriously. It may need changes to the architecture in the system to accomodate for this scenario. For example, in a distributed, service-oriented architecture, where the evolution of the parts should be independent of each other, a discontinous deploy may only cause a temporary downtime (or fallback to readonly) in some part of the whole software system.

A discrete change in the environment may be approximated by lots & lots of continuous changes

ContinuousX is quite a thing in software development. Often you cannot anticipate how the software’s environment changes, short iterations are a very useful method to deal with that. If you get into the practice of working that way, your team may be able to accomodate discrete changes in the software’s environment through a succession of continuous deployments where another team may fail to see a solution. As usual, your mileage may vary, and even a good team can encounter a change so big that no stream of deployments can accomodate the change and a heftier change is required.

Legacy is what you couldn’t change

There is another way to handle a non-continuous change in the software’s environment: We push existing structures beyond their limits. That is, we pervert the existing structure’s intent and reinterpret it to fit to the new environment. While this can certainly work, it means that the software system now makes it harder to see how a given part of the system is related to the software’s environment. This knowledge may now be stored in documentation or maybe just in the team members’ heads. There is a good change that this software system is now far more susceptible to team members leaving, since a new developer, upon reading the code base, may have to deal with concepts which seem oddly detached to what the software user is experiencing. It is also likely that software systems that follow this path may at some point need to be rewritten as its internal shape loses the ability to cope with the software’s environment.

After all, let’s not forget - if the environment moves far away from the one in which the software thrived, the fate of the software may be similar to that of nature’s life forms when they are not fit to cope with the external circumstances: Extinction.